By Sara Bondioli

I hear it time and time again: I would try to homebrew, BUT …

What follows is one (or multiple) reasons someone says they definitely cannot try making beer. And here, I will tell you why they’re absolutely wrong.

Some people really don’t want to homebrew, and that’s fine. I’m not going to look down on you for not wanting to try my hobby. Drink my homebrew. Buy craft beer. Live your life the way you want to.

For the rest of you, let me explain why your reasons for not homebrewing aren’t obstacles at all.

I don’t know where to start.

First, here are some basics about brewing. There are two major classifications of how people homebrew: all-grain and extract.

All-grain brewing is the more time-intensive method. You begin with malted grains that you crush and steep in hot water to convert starches into simple sugars. Then, you boil that sugar water (known as wort), add hops and sometimes other ingredients, cool it down, and add yeast. The yeast eats the sugars, creating alcohol and CO2, and — voila! — you have beer.

Extract brewing is the same process except the first step has already been done for you. Instead of starting by steeping grains, you purchase a syrup (liquid malt extract, LME) or powder (dry malt extract, DME), which is a form of that sugar that someone else has already converted. Thus, you might steep a handful of grains (depending on the recipe) but generally skip directly to boiling water, adding the malt extract and hops, and then cooling to pitch the yeast. In some methods, you boil only a portion of the water and then add cool, clean water at the end to help chill the hot wort.

To get started, you may want to check out a brewing book, such as “How to Brew” by John Palmer or “The Complete Joy of Homebrewing” by Charlie Papazian. A number of sites also have helpful forums where you can find answers to your brewing questions. Check out the American Homebrewers Association, HomeBrewTalk, and Reddit. (Most likely, people have already asked and answered your question there.)

I don’t have space.

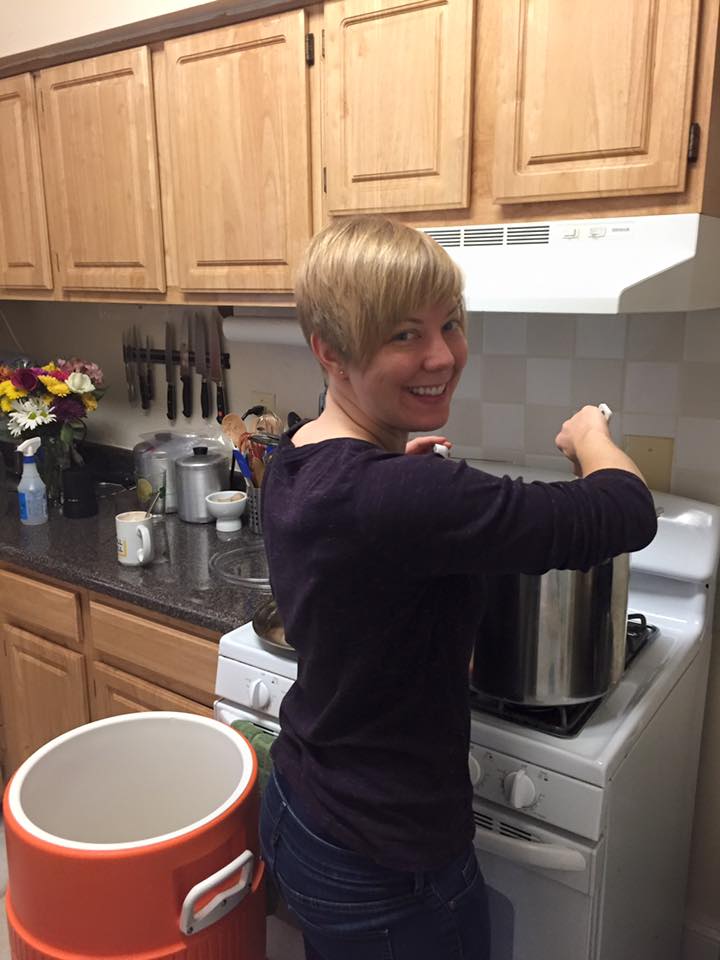

I encountered this a lot while living in Washington, D.C. I get it — space is a premium. I started brewing while living in a 500-square-foot, one-bedroom apartment. I know of people who have brewed in even less space. Maybe you don’t have room for a 10-gallon mash tun, a 15-gallon boil kettle and a kegerator. That’s fine. The great thing about homebrewing is there are hundreds of options.

Start with 1-gallon or 3-gallon batches. I began brewing 1-gallon all-grain batches (basically, the Brooklyn Brew Shop kits). To get started, you just need a 2-gallon or larger stock pot, a strainer and the brewing kit. That doesn’t take up much space. When it’s time to bottle, you’ll also need about 10 bottles, bottle caps and a capper. (I recommend also getting an auto-siphon and bottling wand to make your experience easier.)

I don’t have spare money.

Read the “space” argument above. You can brew small amounts of beer with very little equipment, thus at low cost to you. Instead of buying bottles to fill, you can save bottles from pry-off-cap beers you drink — just clean them (it’s also best to remove the labels; soaking in OxiClean can help with that) and sanitize them. Instead of purchasing a beer kit, you might find it easier to find a recipe online that you want to make and purchase the ingredients individually at a homebrew shop. Many shops allow you to purchase the exact amount of malt you need.

I don’t have time.

The biggest portion of time in brewing is spent waiting — and that means you have time to do other things! You might be fairly busy during your first brew day. But once you get the hang of things, you’ll find that you have downtime while your grains steep in the mash tun, while your wort comes up to a boil and while it boils. And the largest stretch of time is the approximately two weeks it takes for fermentation. During that time, there’s very little you need to do for most beers: Just let it do its thing and make sure your blow-off tube or airlock are still in place.

You also might want to look into extract brewing. It’s a method a lot of brewers start with (and some continue using for decades) because it results in a shorter brew day. See my basic descriptions in the “I don’t know where to start” section.

There’s so much good craft beer, there’s no reason to make my own.

The first part of this is true: There is so much great craft beer these days that it’s hard to even taste everything from your local breweries, much less other breweries selling in your city. You can find a large variety of beers, from classic styles to really out-there combinations.

However, there are still some advantages to making your own. First, you can make exactly the beer you want to drink. There is no limit to what you can dream up. Some of the most memorable and unique homebrews I’ve tasted are a celery kolsch and a pickleback ale.

Second, you have control over the beer. Do you enjoy IPAs? You can ensure the hops you put in your beer are the freshest available. You can drink your homebrewed IPA as soon as it’s ready, when the hop flavor and aroma are at their peak. Like a smooth, aged imperial stout? You can brew that beer and pull out a bottle every few months to see how it’s developing — and then drink the rest when it’s just right for your palate.

Now that you have no excuse not to, what are you going to brew first?